| Berenice (originale) | Berenice (traduzione) |

|---|---|

| MISERY is manifold. | MISERY è molteplice. |

| The wretchedness of earth is multiform. | La miseria della terra è multiforme. |

| Overreaching the | Superare il |

| wide | largo |

| horizon as the rainbow, its hues are as various as the hues of that arch, | orizzonte come l'arcobaleno, le sue sfumature sono varie come le sfumature di quell'arco, |

| —as distinct too, | — anche distinto, |

| yet as intimately blended. | eppure così intimamente mescolati. |

| Overreaching the wide horizon as the rainbow! | Superare l'ampio orizzonte come l'arcobaleno! |

| How is it | Come è |

| that from beauty I have derived a type of unloveliness? | che dalla bellezza ho derivato un tipo di bruttezza? |

| —from the covenant of | —dal patto di |

| peace a | pace A |

| simile of sorrow? | similitudine di dolore? |

| But as, in ethics, evil is a consequence of good, so, in fact, | Ma come, in etica, il male è una conseguenza del bene, così, di fatto, |

| out of joy is | di gioia è |

| sorrow born. | dolore nato. |

| Either the memory of past bliss is the anguish of to-day, | O il ricordo della beatitudine passata è l'angoscia di oggi, |

| or the agonies | o le agonie |

| which are have their origin in the ecstasies which might have been. | che hanno la loro origine nelle estasi che avrebbero potuto essere. |

| My baptismal name is Egaeus; | Il mio nome battesimale è Egaeus; |

| that of my family I will not mention. | quello della mia famiglia non lo citerò. |

| Yet there are no | Eppure non ci sono |

| towers in the land more time-honored than my gloomy, gray, hereditary halls. | torri in una terra più antica delle mie cupe, grigie sale ereditarie. |

| Our line | La nostra linea |

| has been called a race of visionaries; | è stata definita una razza di visionari; |

| and in many striking particulars —in the | e in molti particolari sorprendenti: nel |

| character | carattere |

| of the family mansion —in the frescos of the chief saloon —in the tapestries of | del palazzo di famiglia - negli affreschi del salone principale - negli arazzi di |

| the | il |

| dormitories —in the chiselling of some buttresses in the armory —but more | dormitori — nella cesellatura di alcuni contrafforti nell'armeria — ma altro |

| especially | specialmente |

| in the gallery of antique paintings —in the fashion of the library chamber —and, | nella galleria dei dipinti antichi, alla maniera della camera della biblioteca, e, |

| lastly, | infine, |

| in the very peculiar nature of the library’s contents, there is more than | nella natura molto particolare dei contenuti della biblioteca, c'è più di |

| sufficient | sufficiente |

| evidence to warrant the belief. | prove per giustificare la convinzione. |

| The recollections of my earliest years are connected with that chamber, | I ricordi dei miei primi anni sono legati a quella camera, |

| and with its | e con il suo |

| volumes —of which latter I will say no more. | volumi — di cui quest'ultimo non dirò altro. |

| Here died my mother. | Qui è morta mia madre. |

| Herein was I born. | Qui sono nato. |

| But it is mere idleness to say that I had not lived before | Ma è solo pigrizia dire che non avevo mai vissuto prima |

| —that the | -che il |

| soul has no previous existence. | l'anima non ha un'esistenza precedente. |

| You deny it? | Lo neghi? |

| —let us not argue the matter. | —non discutiamo la questione. |

| Convinced myself, I seek not to convince. | Convinto di me stesso, cerco di non convincere. |

| There is, however, a remembrance of | C'è, tuttavia, un ricordo di |

| aerial | aereo |

| forms —of spiritual and meaning eyes —of sounds, musical yet sad —a remembrance | forme —di occhi spirituali e significanti —di suoni, musicali eppure tristi —un ricordo |

| which will not be excluded; | che non sarà escluso; |

| a memory like a shadow, vague, variable, indefinite, | una memoria come un'ombra, vaga, variabile, indefinita, |

| unsteady; | instabile; |

| and like a shadow, too, in the impossibility of my getting rid of it | e anche come un'ombra, nell'impossibilità che me ne liberi |

| while the | mentre il |

| sunlight of my reason shall exist. | la luce del sole della mia ragione esisterà. |

| In that chamber was I born. | In quella camera sono nato. |

| Thus awaking from the long night of what seemed, | Risvegliandosi così dalla lunga notte di ciò che sembrava, |

| but was | ma era |

| not, nonentity, at once into the very regions of fairy-land —into a palace of | non, nulla, subito nelle stesse regioni del paese delle fate, in un palazzo di |

| imagination | immaginazione |

| —into the wild dominions of monastic thought and erudition —it is not singular | —nei domini selvaggi del pensiero e dell'erudizione monastica —non è singolare |

| that I | che io |

| gazed around me with a startled and ardent eye —that I loitered away my boyhood | mi guardava intorno con uno sguardo sbalordito e ardente, che io indugiavo via la mia fanciullezza |

| in | in |

| books, and dissipated my youth in reverie; | libri, e ho dissipato la mia giovinezza nelle fantasticherie; |

| but it is singular that as years | ma è singolare che come anni |

| rolled away, | rotolato via, |

| and the noon of manhood found me still in the mansion of my fathers —it is | e il meriggio della virilità mi trovò ancora nella dimora dei miei padri... lo è |

| wonderful | meraviglioso |

| what stagnation there fell upon the springs of my life —wonderful how total an | quale ristagno cadde sulle sorgenti della mia vita — meraviglioso quanto totale an |

| inversion took place in the character of my commonest thought. | l'inversione ha avuto luogo nel carattere del mio pensiero più comune. |

| The realities of | Le realtà di |

| the | il |

| world affected me as visions, and as visions only, while the wild ideas of the | mondo mi ha influenzato come visioni, e solo come visioni, mentre le idee selvagge del |

| land of | terra di |

| dreams became, in turn, —not the material of my every-day existence-but in very | i sogni sono diventati, a loro volta, —non il materiale della mia esistenza quotidiana, ma in tutto |

| deed | atto |

| that existence utterly and solely in itself. | quell'esistenza completamente e unicamente in se stessa. |

| - | - |

| Berenice and I were cousins, and we grew up together in my paternal halls. | Berenice ed io eravamo cugine, e siamo cresciute insieme nelle mie sale paterne. |

| Yet differently we grew —I ill of health, and buried in gloom —she agile, | Eppure in modo diverso siamo cresciuti - io malato di salute e sepolto nell'oscurità - lei agile, |

| graceful, and | grazioso, e |

| overflowing with energy; | traboccante di energia; |

| hers the ramble on the hill-side —mine the studies of | lei è la passeggiata sul pendio della collina: i miei studi di |

| the | il |

| cloister —I living within my own heart, and addicted body and soul to the most | chiostro: vivo nel mio cuore e ne sono dipendente dal corpo e dall'anima |

| intense | intenso |

| and painful meditation —she roaming carelessly through life with no thought of | e meditazione dolorosa: lei vagava con noncuranza per la vita senza pensarci |

| the | il |

| shadows in her path, or the silent flight of the ravenwinged hours. | ombre sul suo cammino, o il volo silenzioso delle ore alate di corvo. |

| Berenice! | Berenice! |

| —I call | -Chiamo |

| upon her name —Berenice! | sul suo nome — Berenice! |

| —and from the gray ruins of memory a thousand | — e dalle grigie rovine della memoria mille |

| tumultuous recollections are startled at the sound! | ricordi tumultuosi sono spaventati dal suono! |

| Ah! | Ah! |

| vividly is her image | vividamente è la sua immagine |

| before me | prima di me |

| now, as in the early days of her lightheartedness and joy! | ora, come nei primi giorni della sua spensieratezza e gioia! |

| Oh! | Oh! |

| gorgeous yet | stupendo ancora |

| fantastic | fantastico |

| beauty! | bellezza! |

| Oh! | Oh! |

| sylph amid the shrubberies of Arnheim! | silfide tra i cespugli di Arnheim! |

| —Oh! | -Oh! |

| Naiad among its | Naiade tra i suoi |

| fountains! | fontane! |

| —and then —then all is mystery and terror, and a tale which should not be told. | — e poi — allora tutto è mistero e terrore, e una storia che non dovrebbe essere raccontata. |

| Disease —a fatal disease —fell like the simoom upon her frame, and, even while I | La malattia - una malattia mortale - cadde come il simoom sul suo corpo e, anche mentre io |

| gazed upon her, the spirit of change swept, over her, pervading her mind, | la guardò, lo spirito del cambiamento la investì, pervadendo la sua mente, |

| her habits, | le sue abitudini, |

| and her character, and, in a manner the most subtle and terrible, | e il suo carattere, e, in un modo il più sottile e terribile, |

| disturbing even the | inquietante anche il |

| identity of her person! | identità della sua persona! |

| Alas! | Ahimè! |

| the destroyer came and went, and the victim | il distruttore andava e veniva, e la vittima |

| —where was | -dov'era |

| she, I knew her not —or knew her no longer as Berenice. | lei, non la conoscevo, o non la conoscevo più come Berenice. |

| Among the numerous train of maladies superinduced by that fatal and primary one | Tra il numeroso seguito di malattie sovraindotte da quello fatale e primario |

| which effected a revolution of so horrible a kind in the moral and physical | che ha effettuato una rivoluzione di un tipo così orribile nella morale e fisica |

| being of my | essere del mio |

| cousin, may be mentioned as the most distressing and obstinate in its nature, | cugino, può essere menzionato come il più doloroso e ostinato nella sua natura, |

| a species | una specie |

| of epilepsy not unfrequently terminating in trance itself —trance very nearly | di epilessia che non di rado termina in trance stessa, quasi quasi |

| resembling positive dissolution, and from which her manner of recovery was in | somigliava a una dissoluzione positiva e da cui proveniva il suo modo di riprendersi |

| most | più |

| instances, startlingly abrupt. | casi, sorprendentemente bruschi. |

| In the mean time my own disease —for I have been | Nel frattempo la mia stessa malattia, perché lo sono stata |

| told | detto |

| that I should call it by no other appelation —my own disease, then, | che non dovrei chiamarlo con nessun altro appellativo — la mia stessa malattia, quindi, |

| grew rapidly upon | crebbe rapidamente |

| me, and assumed finally a monomaniac character of a novel and extraordinary | me, e alla fine assunse un carattere monomaniaco di un romanzo e straordinario |

| form — | modulo - |

| hourly and momently gaining vigor —and at length obtaining over me the most | guadagnando vigore ogni ora e al momento, e alla fine ottenendo su di me il massimo |

| incomprehensible ascendancy. | ascendenza incomprensibile. |

| This monomania, if I must so term it, consisted in a morbid irritability of | Questa monomania, se devo chiamarla così, consisteva in una morbosa irritabilità di |

| those | quelli |

| properties of the mind in metaphysical science termed the attentive. | proprietà della mente nella scienza metafisica chiamate l'attento. |

| It is more than | È più di |

| probable that I am not understood; | probabile che non sia compreso; |

| but I fear, indeed, that it is in no manner | ma temo, infatti, che non lo sia in alcun modo |

| possible to | possibile |

| convey to the mind of the merely general reader, an adequate idea of that | trasmettere alla mente del lettore meramente generico un'idea adeguata di ciò |

| nervous | nervoso |

| intensity of interest with which, in my case, the powers of meditation (not to | intensità di interesse con cui, nel mio caso, i poteri della meditazione (non a |

| speak | parlare |

| technically) busied and buried themselves, in the contemplation of even the most | tecnicamente) si davano da fare e si seppellivano, nella contemplazione anche dei più |

| ordinary objects of the universe. | oggetti ordinari dell'universo. |

| To muse for long unwearied hours with my attention riveted to some frivolous | Per rimuginare per lunghe ore instancabili con la mia attenzione inchiodata a qualche frivola |

| device | dispositivo |

| on the margin, or in the topography of a book; | a margine o nella topografia di un libro; |

| to become absorbed for the | di essere assorbito per il |

| better part of | parte migliore di |

| a summer’s day, in a quaint shadow falling aslant upon the tapestry, | un giorno d'estate, in un'ombra pittoresca che cade di sbieco sull'arazzo, |

| or upon the door; | o sulla porta; |

| to lose myself for an entire night in watching the steady flame of a lamp, | perdermi per un'intera notte a guardare la fiamma costante di una lampada, |

| or the embers | o le braci |

| of a fire; | di un incendio; |

| to dream away whole days over the perfume of a flower; | sognare giorni interi al profumo di un fiore; |

| to repeat | ripetere |

| monotonously some common word, until the sound, by dint of frequent repetition, | monotonamente qualche parola comune, finché il suono, a forza di frequenti ripetizioni, |

| ceased to convey any idea whatever to the mind; | ha smesso di trasmettere qualsiasi idea alla mente; |

| to lose all sense of motion or | per perdere il senso del movimento o |

| physical | fisico |

| existence, by means of absolute bodily quiescence long and obstinately | esistenza, per mezzo di un'assoluta quiescenza corporea lunga e ostinata |

| persevered in; | perseverato; |

| —such were a few of the most common and least pernicious vagaries induced by a | — tali erano alcuni dei capricci più comuni e meno perniciosi indotti da a |

| condition of the mental faculties, not, indeed, altogether unparalleled, | condizione delle facoltà mentali, non del tutto impareggiabile, |

| but certainly | ma certamente |

| bidding defiance to anything like analysis or explanation. | offrendo sfida a qualsiasi cosa come analisi o spiegazione. |

| Yet let me not be misapprehended. | Tuttavia, non lasciarmi fraintendere. |

| —The undue, earnest, and morbid attention thus | - L'attenzione indebita, seria e morbosa, quindi |

| excited by objects in their own nature frivolous, must not be confounded in | eccitati da oggetti per loro natura frivoli, non devono essere confusi |

| character | carattere |

| with that ruminating propensity common to all mankind, and more especially | con quella propensione rimuginante comune a tutta l'umanità, e più specialmente |

| indulged | assecondato |

| in by persons of ardent imagination. | in da persone di fervida immaginazione. |

| It was not even, as might be at first | Non era nemmeno, come potrebbe essere all'inizio |

| supposed, an | supposto, un |

| extreme condition or exaggeration of such propensity, but primarily and | condizione estrema o esagerazione di tale propensione, ma principalmente e |

| essentially | essenzialmente |

| distinct and different. | distinti e diversi. |

| In the one instance, the dreamer, or enthusiast, | In un caso, il sognatore, o entusiasta, |

| being interested | essere interessato |

| by an object usually not frivolous, imperceptibly loses sight of this object in | da un oggetto di solito non frivolo, perde impercettibilmente di vista questo oggetto in |

| wilderness of deductions and suggestions issuing therefrom, until, | deserto di deduzioni e suggerimenti che ne derivano, finché, |

| at the conclusion of | a conclusione di |

| a day dream often replete with luxury, he finds the incitamentum or first cause | un sogno ad occhi aperti spesso pieno di lusso, trova l'incitamentum o la prima causa |

| of his | del suo |

| musings entirely vanished and forgotten. | riflessioni del tutto svanite e dimenticate. |

| In my case the primary object was | Nel mio caso l'oggetto principale era |

| invariably | invariabilmente |

| frivolous, although assuming, through the medium of my distempered vision, a | frivolo, sebbene presupponendo, per mezzo della mia visione temperata, a |

| refracted and unreal importance. | importanza rifratta e irreale. |

| Few deductions, if any, were made; | Sono state effettuate poche detrazioni, se ve ne sono state; |

| and those few | e quei pochi |

| pertinaciously returning in upon the original object as a centre. | ritornando pertinacemente sull'oggetto originale come un centro. |

| The meditations were | Le meditazioni erano |

| never pleasurable; | mai piacevole; |

| and, at the termination of the reverie, the first cause, | e, al termine della rêverie, la causa prima, |

| so far from | così lontano da |

| being out of sight, had attained that supernaturally exaggerated interest which | essendo fuori dalla vista, aveva raggiunto quell'interesse soprannaturalmente esagerato che |

| was the | era la |

| prevailing feature of the disease. | caratteristica prevalente della malattia. |

| In a word, the powers of mind more | In una parola, i poteri della mente di più |

| particularly | in particolar modo |

| exercised were, with me, as I have said before, the attentive, and are, | esercitato erano, con me, come ho detto prima, l'attento, e sono, |

| with the daydreamer, | con il sognatore ad occhi aperti, |

| the speculative. | lo speculativo. |

| My books, at this epoch, if they did not actually serve to irritate the | I miei libri, in questa epoca, se non servissero effettivamente a irritare il |

| disorder, partook, it | disordine, partecipò, esso |

| will be perceived, largely, in their imaginative and inconsequential nature, | saranno percepiti, in gran parte, nella loro natura fantasiosa e irrilevante, |

| of the | del |

| characteristic qualities of the disorder itself. | qualità caratteristiche del disturbo stesso. |

| I well remember, among others, | Ricordo bene, tra gli altri, |

| the treatise | il trattato |

| of the noble Italian Coelius Secundus Curio «de Amplitudine Beati Regni dei»; | del nobile italiano Coelius Secundus Curio «de Amplitudine Beati Regni dei»; |

| St. | S. |

| Austin’s great work, the «City of God»; | la grande opera di Austin, la «Città di Dio»; |

| and Tertullian «de Carne Christi,» | e Tertulliano «de Carne Christi», |

| in which the | in cui la |

| paradoxical sentence «Mortuus est Dei filius; | frase paradossale «Mortuus est Dei filius; |

| credible est quia ineptum est: | credibile est quia ineptum est: |

| et sepultus | et sepultus |

| resurrexit; | risurrezione; |

| certum est quia impossibile est» occupied my undivided time, | certum est quia impossibile est» ha occupato il mio tempo indiviso, |

| for many | per molti |

| weeks of laborious and fruitless investigation. | settimane di indagine laboriosa e infruttuosa. |

| Thus it will appear that, shaken from its balance only by trivial things, | Così sembrerà che, scosso dal suo equilibrio solo da cose banali, |

| my reason bore | la mia ragione annoia |

| resemblance to that ocean-crag spoken of by Ptolemy Hephestion, which steadily | somiglianza con quella rupe oceanica di cui parla Tolomeo Efestione, che costantemente |

| resisting the attacks of human violence, and the fiercer fury of the waters and | resistere agli attacchi della violenza umana e alla furia più feroce delle acque e |

| the | il |

| winds, trembled only to the touch of the flower called Asphodel. | venti, tremavano solo al tocco del fiore chiamato Asfodelo. |

| And although, to a careless thinker, it might appear a matter beyond doubt, | E sebbene, a un pensatore distratto, possa sembrare una questione fuori dubbio, |

| that the | che il |

| alteration produced by her unhappy malady, in the moral condition of Berenice, | alterazione prodotta dalla sua infelice malattia, nella condizione morale di Berenice, |

| would | voluto |

| afford me many objects for the exercise of that intense and abnormal meditation | concedimi molti oggetti per l'esercizio di quella meditazione intensa e anormale |

| whose | il cui, di chi |

| nature I have been at some trouble in explaining, yet such was not in any | natura che ho avuto qualche difficoltà a spiegare, ma questo non era in nessuno |

| degree the | grado il |

| case. | Astuccio. |

| In the lucid intervals of my infirmity, her calamity, indeed, | Nei lucidi intervalli della mia infermità, la sua calamità, infatti, |

| gave me pain, and, | mi ha dato dolore e |

| taking deeply to heart that total wreck of her fair and gentle life, | prendendo profondamente a cuore quel totale relitto della sua vita bella e gentile, |

| I did not fall to ponder | Non sono caduto a riflettere |

| frequently and bitterly upon the wonderworking means by which so strange a | spesso e amaramente sui mezzi miracolosi con cui a |

| revolution had been so suddenly brought to pass. | la rivoluzione era stata compiuta così all'improvviso. |

| But these reflections partook | Ma queste riflessioni hanno partecipato |

| not of | non di |

| the idiosyncrasy of my disease, and were such as would have occurred, | l'idiosincrasia della mia malattia, ed erano tali che si sarebbero verificati, |

| under similar | sotto simili |

| circumstances, to the ordinary mass of mankind. | circostanze, alla massa ordinaria dell'umanità. |

| True to its own character, | Fedele al proprio carattere, |

| my disorder | il mio disturbo |

| revelled in the less important but more startling changes wrought in the | si dilettava nei cambiamenti meno importanti ma più sorprendenti apportati nel |

| physical frame | cornice fisica |

| of Berenice —in the singular and most appalling distortion of her personal | di Berenice, nella singolare e spaventosa distorsione del suo personale |

| identity. | identità. |

| During the brightest days of her unparalleled beauty, most surely I had never | Durante i giorni più luminosi della sua bellezza senza pari, sicuramente non l'ho mai fatto |

| loved | amato |

| her. | suo. |

| In the strange anomaly of my existence, feelings with me, had never been | Nella strana anomalia della mia esistenza, i sentimenti con me non erano mai stati |

| of the | del |

| heart, and my passions always were of the mind. | cuore, e le mie passioni sono sempre state della mente. |

| Through the gray of the early | Attraverso il grigio dei primi |

| morning —among the trellissed shadows of the forest at noonday —and in the | mattina - tra le ombre a graticcio della foresta a mezzogiorno - e nel |

| silence | silenzio |

| of my library at night, she had flitted by my eyes, and I had seen her —not as | della mia biblioteca di notte, era passata davanti ai miei occhi e io l'avevo vista, non come |

| the living | i vivi |

| and breathing Berenice, but as the Berenice of a dream —not as a being of the | e respira Berenice, ma come Berenice di un sogno, non come essere del |

| earth, | terra, |

| earthy, but as the abstraction of such a being-not as a thing to admire, | terroso, ma come l'astrazione di un tale essere, non come una cosa da ammirare, |

| but to analyze — | ma per analizzare — |

| not as an object of love, but as the theme of the most abstruse although | non come oggetto d'amore, ma come tema del più astruso però |

| desultory | saltuario |

| speculation. | speculazione. |

| And now —now I shuddered in her presence, and grew pale at her | E ora... ora rabbrividivo in sua presenza e diventavo pallido davanti a lei |

| approach; | approccio; |

| yet bitterly lamenting her fallen and desolate condition, | ma piangendo amaramente la sua condizione decaduta e desolata, |

| I called to mind that | L'ho chiamato per ricordarlo |

| she had loved me long, and, in an evil moment, I spoke to her of marriage. | mi amava da molto tempo e, in un momento malvagio, le parlavo del matrimonio. |

| And at length the period of our nuptials was approaching, when, upon an | E alla fine si avvicinava il periodo delle nostre nozze, quando, su an |

| afternoon in | pomeriggio in |

| the winter of the year, —one of those unseasonably warm, calm, and misty days | l'inverno dell'anno, uno di quei giorni insolitamente caldi, calmi e nebbiosi |

| which | quale |

| are the nurse of the beautiful Halcyon1, —I sat, (and sat, as I thought, alone, | sono la nutrice della bella Halcyon1, — sedevo, (e sedevo, come pensavo, da sola, |

| ) in the | ) nel |

| inner apartment of the library. | appartamento interno della biblioteca. |

| But uplifting my eyes I saw that Berenice stood | Ma alzando gli occhi ho visto che Berenice era in piedi |

| before | prima |

| me. | me. |

| - | - |

| Was it my own excited imagination —or the misty influence of the atmosphere —or | Era la mia stessa eccitata immaginazione o l'influenza nebbiosa dell'atmosfera o |

| the | il |

| uncertain twilight of the chamber —or the gray draperies which fell around her | il crepuscolo incerto della camera, o i tendaggi grigi che le cadevano intorno |

| figure | figura |

| —that caused in it so vacillating and indistinct an outline? | -che ha causato in esso un profilo così vacillante e indistinto? |

| I could not tell. | Non potrei dirlo. |

| She spoke no | Lei ha parlato di no |

| word, I —not for worlds could I have uttered a syllable. | parola, io... non per mondi avrei potuto pronunciare una sillaba. |

| An icy chill ran | Corse un brivido gelido |

| through my | attraverso il mio |

| frame; | telaio; |

| a sense of insufferable anxiety oppressed me; | un senso di insopportabile ansietà mi opprimeva; |

| a consuming curiosity | una curiosità consumante |

| pervaded | pervaso |

| my soul; | la mia anima; |

| and sinking back upon the chair, I remained for some time breathless | e sprofondando sulla sedia, rimasi per qualche tempo senza fiato |

| and | e |

| motionless, with my eyes riveted upon her person. | immobile, con gli occhi fissi sulla sua persona. |

| Alas! | Ahimè! |

| its emaciation was | la sua emaciazione era |

| excessive, | eccessivo, |

| and not one vestige of the former being, lurked in any single line of the | e non una traccia del primo essere, in agguato in nessuna singola linea del |

| contour. | contorno. |

| My | Mio |

| burning glances at length fell upon the face. | sguardi infuocati alla fine caddero sul viso. |

| The forehead was high, and very pale, and singularly placid; | La fronte era alta, e molto pallida, e singolarmente placida; |

| and the once jetty | e il molo di una volta |

| hair fell | i capelli sono caduti |

| partially over it, and overshadowed the hollow temples with innumerable | parzialmente su di esso, e oscurava le tempie cave con innumerevoli |

| ringlets now | riccioli ora |

| of a vivid yellow, and Jarring discordantly, in their fantastic character, | di un giallo vivido, e stridendo discordantemente, nel loro carattere fantastico, |

| with the | con il |

| reigning melancholy of the countenance. | malinconia regnante del volto. |

| The eyes were lifeless, and lustreless, | Gli occhi erano senza vita e senza lucentezza, |

| and | e |

| seemingly pupil-less, and I shrank involuntarily from their glassy stare to the | apparentemente senza pupille, e mi sono rimpicciolito involontariamente dal loro sguardo vitreo al |

| contemplation of the thin and shrunken lips. | contemplazione delle labbra sottili e rimpicciolite. |

| They parted; | Si separarono; |

| and in a smile of | e in un sorriso di |

| peculiar | peculiare |

| meaning, the teeth of the changed Berenice disclosed themselves slowly to my | nel senso, i denti della mutata Berenice si sono svelati lentamente ai miei |

| view. | Visualizza. |

| Would to God that I had never beheld them, or that, having done so, I had died! | Volesse Dio che non li avessi mai visti, o che, dopo averlo fatto, fossi morto! |

| 1 For as Jove, during the winter season, gives twice seven days of warmth, | 1 Poiché, come Giove, durante la stagione invernale, dà due volte sette giorni di calore, |

| men have | gli uomini hanno |

| called this clement and temperate time the nurse of the beautiful Halcyon | chiamò questo tempo clemente e temperato la nutrice della bella Alcione |

| —Simonides. | — Simonide. |

| The shutting of a door disturbed me, and, looking up, I found that my cousin had | La chiusura di una porta mi turbò e, alzando gli occhi, scoprii che mio cugino aveva |

| departed from the chamber. | partì dalla camera. |

| But from the disordered chamber of my brain, had not, | Ma dalla camera disordinata del mio cervello, non aveva, |

| alas! | ahimè! |

| departed, and would not be driven away, the white and ghastly spectrum of | se ne andò, e non sarebbe stato scacciato, lo spettro bianco e spettrale di |

| the | il |

| teeth. | denti. |

| Not a speck on their surface —not a shade on their enamel —not an | Non un granello sulla loro superficie, non una sfumatura sul loro smalto, non un |

| indenture in | contratto in |

| their edges —but what that period of her smile had sufficed to brand in upon my | i loro contorni, ma ciò che quel periodo del suo sorriso era bastato a marchiare su di me |

| memory. | memoria. |

| I saw them now even more unequivocally than I beheld them then. | Li vidi ora ancora più inequivocabilmente di quanto li vedessi allora. |

| The teeth! | I denti! |

| —the teeth! | -i denti! |

| —they were here, and there, and everywhere, and visibly and palpably | — erano qui, e là, e dappertutto, e visibilmente e palpabilmente |

| before me; | prima di me; |

| long, narrow, and excessively white, with the pale lips writhing | lunga, stretta ed eccessivamente bianca, con le labbra pallide che si contorcono |

| about them, | su di loro, |

| as in the very moment of their first terrible development. | come nel momento stesso del loro primo terribile sviluppo. |

| Then came the full | Poi è arrivato il pieno |

| fury of my | furia del mio |

| monomania, and I struggled in vain against its strange and irresistible | monomania, e ho lottato invano contro il suo strano e irresistibile |

| influence. | influenza. |

| In the | Nel |

| multiplied objects of the external world I had no thoughts but for the teeth. | oggetti moltiplicati del mondo esterno non avevo pensieri se non per i denti. |

| For these I | Per questi I |

| longed with a phrenzied desire. | bramato con un desiderio frenetico. |

| All other matters and all different interests | Tutte le altre questioni e tutti i diversi interessi |

| became | divennero |

| absorbed in their single contemplation. | assorbiti nella loro unica contemplazione. |

| They —they alone were present to the | Loro — loro soli erano presenti al |

| mental | mentale |

| eye, and they, in their sole individuality, became the essence of my mental | occhio, e loro, nella loro unica individualità, sono diventati l'essenza della mia mente |

| life. | vita. |

| I held | Lo tenevo |

| them in every light. | loro in ogni luce. |

| I turned them in every attitude. | Li ho trasformati in ogni atteggiamento. |

| I surveyed their | Ho sondato il loro |

| characteristics. | caratteristiche. |

| I | io |

| dwelt upon their peculiarities. | soffermandosi sulle loro peculiarità. |

| I pondered upon their conformation. | Ho medito sulla loro conformazione. |

| I mused upon the | Ho rimuginato sul |

| alteration in their nature. | alterazione della loro natura. |

| I shuddered as I assigned to them in imagination a | Rabbrividii mentre li assegnavo nell'immaginazione a |

| sensitive | sensibile |

| and sentient power, and even when unassisted by the lips, a capability of moral | e potere senziente, e anche quando non assistito dalle labbra, una capacità di moralità |

| expression. | espressione. |

| Of Mad’selle Salle it has been well said, «que tous ses pas etaient | Di Mad'selle Salle è stato ben detto, «que tous ses pas etaient |

| des | des |

| sentiments,» and of Berenice I more seriously believed que toutes ses dents | sentimenti», e di Berenice credevo più seriamente a que toutes ses dents |

| etaient des | etaient des |

| idees. | idee. |

| Des idees! | Le idee! |

| —ah here was the idiotic thought that destroyed me! | —ah ecco il pensiero idiota che mi ha distrutto! |

| Des idees! | Le idee! |

| —ah | -ah |

| therefore it was that I coveted them so madly! | quindi è stato che li ho bramati così pazzamente! |

| I felt that their possession | Ho sentito che il loro possesso |

| could alone | potrebbe da solo |

| ever restore me to peace, in giving me back to reason. | mai ristabilirmi alla pace, nel ridarmi alla ragione. |

| And the evening closed in upon me thus-and then the darkness came, and tarried, | E la sera si chiuse su di me così, e poi venne l'oscurità, e si trattenne, |

| and | e |

| went —and the day again dawned —and the mists of a second night were now | se ne andò - e il giorno sorse di nuovo - e le nebbie di una seconda notte erano ora |

| gathering around —and still I sat motionless in that solitary room; | radunandomi intorno - e ancora sedevo immobile in quella stanza solitaria; |

| and still I sat buried | e ancora sedevo sepolto |

| in meditation, and still the phantasma of the teeth maintained its terrible | in meditazione, e ancora il fantasma dei denti manteneva il suo terribile |

| ascendancy | ascendenza |

| as, with the most vivid hideous distinctness, it floated about amid the | mentre, con la più vivida e orribile nitidezza, galleggiava in mezzo al |

| changing lights | luci che cambiano |

| and shadows of the chamber. | e le ombre della camera. |

| At length there broke in upon my dreams a cry as of | Alla fine, nei miei sogni irruppe un grido |

| horror and dismay; | orrore e sgomento; |

| and thereunto, after a pause, succeeded the sound of troubled | e a ciò, dopo una pausa, successe il suono di turbato |

| voices, intermingled with many low moanings of sorrow, or of pain. | voci, mescolate a molti lamenti bassi di dolore, o di dolore. |

| I arose from my | Sono nato dal mio |

| seat and, throwing open one of the doors of the library, saw standing out in the | sedile e, spalancando una delle porte della biblioteca, vide stagliarsi nel |

| antechamber a servant maiden, all in tears, who told me that Berenice was —no | anticamera una serva, tutta in lacrime, che mi ha detto che Berenice era... no |

| more. | di più. |

| She had been seized with epilepsy in the early morning, and now, | Era stata colta da epilessia al mattino presto e ora, |

| at the closing in of | alla chiusura del |

| the night, the grave was ready for its tenant, and all the preparations for the | la notte, la tomba era pronta per il suo inquilino, e tutti i preparativi per il |

| burial | sepoltura |

| were completed. | sono stati completati. |

| I found myself sitting in the library, and again sitting there | Mi sono ritrovato seduto in biblioteca e di nuovo seduto lì |

| alone. | solo. |

| It | Esso |

| seemed that I had newly awakened from a confused and exciting dream. | sembrava che mi fossi appena svegliato da un sogno confuso ed eccitante. |

| I knew that it | Lo sapevo |

| was now midnight, and I was well aware that since the setting of the sun | era ormai mezzanotte, e lo sapevo bene fin dal tramonto del sole |

| Berenice had | Berenice aveva |

| been interred. | stato sepolto. |

| But of that dreary period which intervened I had no positive —at | Ma di quel periodo tetro che è intervenuto non ho avuto alcun riscontro positivo - a |

| least | meno |

| no definite comprehension. | nessuna comprensione definitiva. |

| Yet its memory was replete with horror —horror more | Eppure la sua memoria era piena di orrore, orrore di più |

| horrible from being vague, and terror more terrible from ambiguity. | orribile per essere vago, e terrore più terribile per ambiguità. |

| It was a fearful | È stato pauroso |

| page in the record my existence, written all over with dim, and hideous, and | pagina nel registro la mia esistenza, scritta dappertutto con tenue e orribile, e |

| unintelligible recollections. | ricordi incomprensibili. |

| I strived to decypher them, but in vain; | Mi sono sforzato di decifrarli, ma invano; |

| while ever and | mentre mai e |

| anon, like the spirit of a departed sound, the shrill and piercing shriek of a | anon, come lo spirito di un suono scomparso, l'urlo acuto e penetrante di un |

| female voice | voce femminile |

| seemed to be ringing in my ears. | sembrava che mi risuonasse nelle orecchie. |

| I had done a deed —what was it? | Avevo fatto un atto: cos'era? |

| I asked myself the | Mi sono chiesto il |

| question aloud, and the whispering echoes of the chamber answered me, «what was | domanda ad alta voce, e gli echi sussurri della camera mi risposero: «che cosa era |

| it?» | esso?" |

| On the table beside me burned a lamp, and near it lay a little box. | Sul tavolo accanto a me bruciava una lampada e vicino ad essa c'era una scatoletta. |

| It was of no | Era di n |

| remarkable character, and I had seen it frequently before, for it was the | personaggio straordinario, e l'avevo visto spesso prima, perché era il |

| property of the | proprietà del |

| family physician; | medico di famiglia; |

| but how came it there, upon my table, and why did I shudder in | ma come è successo lì, sulla mia tavola, e perché sono rabbrividito |

| regarding it? | a riguardo? |

| These things were in no manner to be accounted for, and my eyes at | Queste cose non dovevano essere in alcun modo spiegate, e i miei occhi li guardavano |

| length dropped to the open pages of a book, and to a sentence underscored | lunghezza ridotta alle pagine aperte di un libro e a una frase sottolineata |

| therein. | in essa. |

| The | Il |

| words were the singular but simple ones of the poet Ebn Zaiat, «Dicebant mihi sodales | parole erano quelle singolari ma semplici del poeta Ebn Zaiat, «Dicebant mihi sodales |

| si sepulchrum amicae visitarem, curas meas aliquantulum fore levatas. | si sepulchrum amicae visitarem, curas meas aliquantulum fore levatas. |

| «Why then, as I | «Perché allora, come I |

| perused them, did the hairs of my head erect themselves on end, and the blood | li scrutai, i capelli della mia testa si rizzarono e il sangue |

| of my | del mio |

| body become congealed within my veins? | il corpo si è congelato nelle mie vene? |

| There came a light tap at the library | C'è stato un tocco leggero alla libreria |

| door, | porta, |

| and pale as the tenant of a tomb, a menial entered upon tiptoe. | e pallido come l'affittuario di una tomba, un umile entrò in punta di piedi. |

| His looks were | Il suo aspetto era |

| wild | selvaggio |

| with terror, and he spoke to me in a voice tremulous, husky, and very low. | con terrore, e mi parlò con voce tremula, roca e molto bassa. |

| What said | Che cosa ha detto |

| he? | lui? |

| —some broken sentences I heard. | — alcune frasi spezzate che ho sentito. |

| He told of a wild cry disturbing the | Raccontava di un grido selvaggio che disturbava il |

| silence of the | silenzio del |

| night —of the gathering together of the household-of a search in the direction | notte - del raduno della famiglia- di una ricerca nella direzione |

| of the | del |

| sound; | suono; |

| —and then his tones grew thrillingly distinct as he whispered me of a | — e poi i suoi toni si fecero straordinariamente distinti mentre mi sussurrava di a |

| violated | violato |

| grave —of a disfigured body enshrouded, yet still breathing, still palpitating, | tomba - di un corpo sfigurato avvolto, ma ancora respirante, ancora palpitante, |

| still alive! | ancora vivo! |

| He pointed to garments;-they were muddy and clotted with gore. | Indicò gli indumenti; erano fangosi e raggrumati di sangue. |

| I spoke not, | Non ho parlato, |

| and he | e lui |

| took me gently by the hand; | mi prese gentilmente per mano; |

| —it was indented with the impress of human nails. | —era dentellato con l'impronta di unghie umane. |

| He | Lui |

| directed my attention to some object against the wall; | indirizzato la mia attenzione a qualche oggetto contro il muro; |

| —I looked at it for some | —L'ho guardato per alcuni |

| minutes; | minuti; |

| —it was a spade. | —era una vanga. |

| With a shriek I bounded to the table, and grasped the box that | Con uno strillo mi balzai al tavolo e afferro la scatola |

| lay | posizione |

| upon it. | su di essa. |

| But I could not force it open; | Ma non potevo forzarlo ad aprirlo; |

| and in my tremor it slipped from my | e nel mio tremore è scivolato dal mio |

| hands, and | mani, e |

| fell heavily, and burst into pieces; | cadde pesantemente ed esplose in pezzi; |

| and from it, with a rattling sound, | e da esso, con un suono sferragliante, |

| there rolled out | lì è uscito |

| some instruments of dental surgery, intermingled with thirty-two small, | alcuni strumenti di chirurgia dentale, frammisti a trentadue piccoli, |

| white and | bianco e |

| ivory-looking substances that were scattered to and fro about the floor. | sostanze dall'aspetto avorio sparse qua e là per il pavimento. |

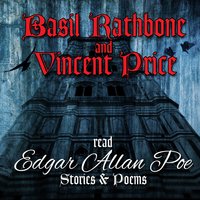

Traduzione del testo della canzone Berenice - Vincent Price, Basil Rathbone

Informazioni sulla canzone In questa pagina puoi leggere il testo della canzone Berenice , di -Vincent Price

Nel genere:Саундтреки

Data di rilascio:14.08.2013

Seleziona la lingua in cui tradurre:

Scrivi cosa pensi del testo!

Altre canzoni dell'artista:

| Nome | Anno |

|---|---|

| 2013 | |

| 2013 | |

| 2013 | |

| 2013 |